Find out when Google last rendered your site

By now it’s clear to us that Googlebot renders JavaScript. That is, it doesn’t interact with JS, but it is capable of crawling the JS that modifies the website’s DOM and, therefore, it is able to see the content (as long as it is indexable and crawlable) of websites built with CSR.

Careful: Google is able to do this and does it reasonably well. However, JavaScript is invisible to all LLMs with the possible exception of Gemini.

The point is that even though Google is capable, the rendering process is an expensive and resource-intensive process for Google. Google does not crawl directly with JavaScript. It crawls without JavaScript and then passes it to its microservice WRS (Web Rendering Service). This way, by rendering only the websites they have cached, they can render the JS of all websites without the process being so costly that it becomes uneconomical for them. (I always use the example that when you crawl with Screaming Frog, with and without JS, you can see a big difference in the total time it takes to crawl the site— now multiply that by all the websites Google has to crawl.)

The truth is that this technique Google uses can cause our dates to differ. The moment when Google crawled our site is not the same as the last moment when it rendered our site, since it does those at different times.

It can be interesting to know how often Google crawls our website and its pages.

Spoiler: even though we have the term “crawl budget”, depending on the page or groups of pages, even within the same site, Google will crawl and render them with different frequencies.

To find out whether Google is already aware of a change we made on the site, there is a fairly easy way to do it via crawling, but I’m also going to show you how to do it with rendering.

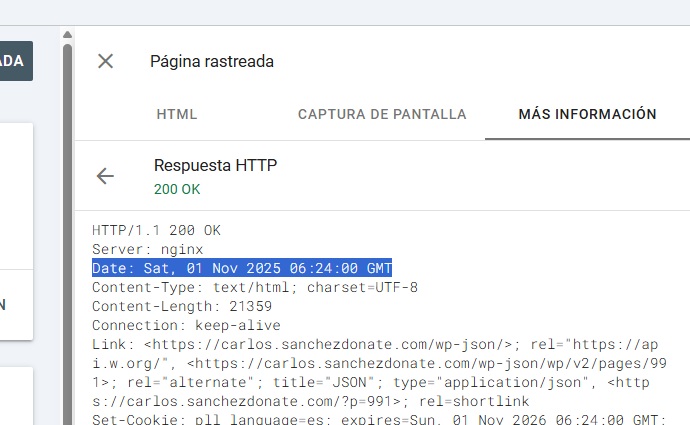

If we stick to Search Console, we can see the HTTP response that our site gave to Google’s crawler.

We could do this by inspecting a URL in Search Console WITHOUT CLICKING ON "TEST LIVE URL"; in theory, we would be able to see the last time it crawled us.

However, this information is incomplete.

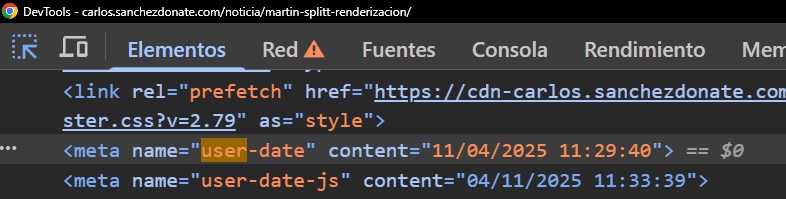

I suggest adding the current time in 2 custom meta tags using the server-side language your site uses (PHP in the case of WordPress).

<meta name="user-date" content="<?php date_default_timezone_set('Europe/Madrid'); $date = date('m/d/Y H:i:s');echo $date;?>"> <meta name="user-date-js" content="<?php date_default_timezone_set('Europe/Madrid'); $date = date('m/d/Y H:i:s');echo $date;?>">

A script to set the date in real time with JS (since in PHP you’ll get the date from the response header):

function updateMetaDate() {

const metaTag = document.querySelector('meta[name="user-date-js"]');

if (metaTag) {

setInterval(() => {

const now = new Date();

const formattedDate = now.toLocaleString('es-ES', {

year: 'numeric',

month: '2-digit',

day: '2-digit',

hour: '2-digit',

minute: '2-digit',

second: '2-digit'

}).replace(',', '');

metaTag.setAttribute('content', formattedDate);

}, 1000);

}

}

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", updateMetaDate);te);

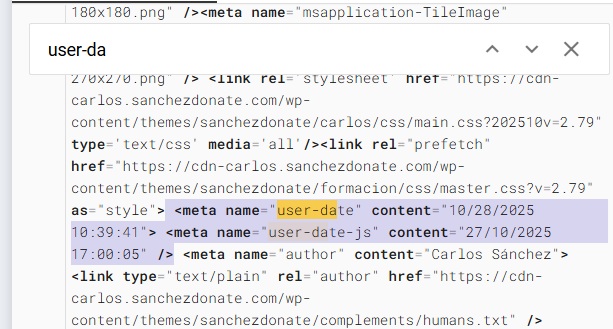

This way, in the meta tags in your <head> you’ll see these two: one that captures the moment of the request and another with the current time:

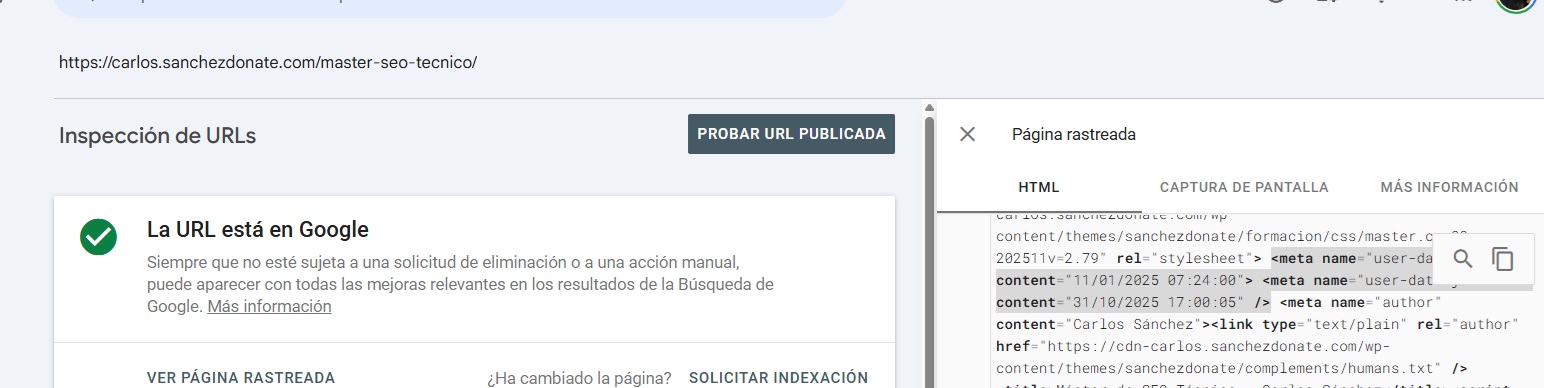

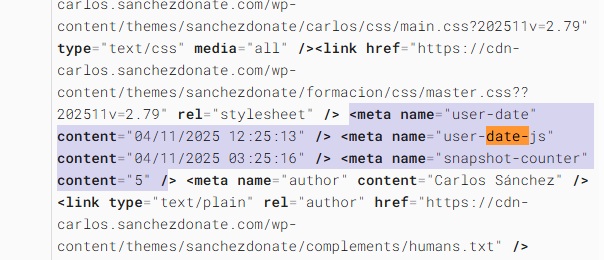

So once we have the site’s code done, all that’s left is to audit it through Search Console.

When you’re sure that Google has already crawled the latest version of your page, you must inspect the URL whose snapshot you want to check WITHOUT CLICKING ON “TEST LIVE URL” and check the time difference.

There will be a difference between your server’s exact time and Google’s JS time (of course, they crawl from the US).

But you can see how many seconds it takes them to take the snapshot on your site. In this case it shows me the following:

<meta name="user-date" content="11/01/2025 07:24:00"> <!-- Día 1 de noviembre -->

<meta name="user-date-js" content="31/10/2025 17:00:05" /> <!-- Día 31 de octubre -->

If we ignore the time zone and how useless I was with the date format, we can see that it was rendered practically the day after the crawl. And that the HTTP header response corresponds to the crawl, not to the moment when the JS rendering and DOM update were done.

In this example, little time has passed, but there are other pages with lower crawl frequency where you can even see that the last crawl date is more recent than the last rendering, for example:

TESTING PHASE, I’LL UPDATE WITH ANY NEW FINDINGS

Google takes a snapshot of the site with JavaScript; Martin Splitt explained that there is a delay before rendering is done. This is because websites are “alive,” and any browser has to download the JavaScript, process it, and apply the changes in the DOM along with any related animations to produce the final result.

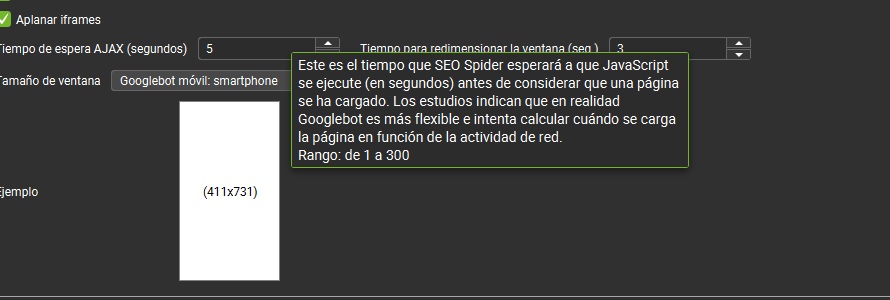

What Google’s representatives tell us is that it takes about 5 seconds. This tells us that WPO can affect rendering. But what we’re interested in is accurately calculating the real snapshot time.

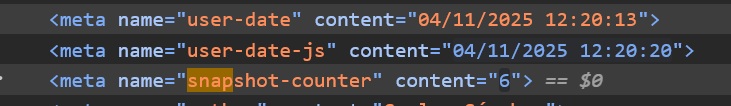

To calculate the exact snapshot time and see whether it has properly rendered the relevant JS, I’ve added this other custom meta tag:

If I get a plausible result, I’ll share in this same post how to set the same average time Google takes to render us in Screaming Frog, so we can have information that’s as realistic as possible for our audits.

Example of the script we could use for the counter in that meta tag:

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', () => {

const meta = document.querySelector('meta[name="snapshot-counter"]');

let count = parseInt(meta.getAttribute('content')) || 0;

const intervalId = setInterval(() => {

count++;

meta.setAttribute('content', count.toString());

console.log('Contador actualizado a:', count);

const currentValue = meta.getAttribute('content');

console.log('Valor en el DOM:', currentValue);

}, 1000);

window.snapshotIntervalId = intervalId;

});

If we click on “Test Live URL,” what we’re doing is a live testing; it won’t be Google’s real crawl for its actual ranking mechanism, but rather a test of “how it would look if Google crawled this URL right now.”

This tool is very useful and interesting; it even helps us detect errors that we wouldn’t see just from the final DOM.

It serves as proof that in Live it takes 5 seconds (let’s consider the counter to be more reliable than the date difference— if you’re interested, I can explain why) to take the snapshot:

But as I said, Live is for testing, not for the final check.

This post on my website was written in appreciation of a publication by SEO specialist Marcela Lopez, since this kind of social media content motivates me to keep creating more.

I currently offer advanced SEO training in Spanish. Would you like me to create an English version? Let me know!

Tell me you're interested