How to Debug, Test & Control What Google Sees

Notice to the reader:

This is an article I created for Sitebulb with great care. You can read the original article here.

Carlos Sanchez shares a developer-driven and experimental guide to debugging rendering issues.

In SEO, rendering isn’t just about JavaScript. It’s the complete process of how browsers and search engines interpret your HTML, CSS, and JS to understand your content.

Humans do not process code in real time. Code is transformed into pixels, which allow us to visually comprehend what a website is trying to convey. This process of transformation and interpretation is known as rendering.

S earch engines and LLMs do not need to convert the code into a visual format to understand its content. However, they must still interpret it in order to process the information and determine whether it would be relevant to a human. For this reason, search engines and LLMs also have their own rendering process.

💡 Editorial Note:

This article is part of our Rendering in SEO mini-series, where SEO experts explore how search engines and AI systems understand your website.

In the JavaScript SEO Fundamentals Guide to Web Rendering Techniques by Matt Hollingshead, you learn how different rendering frameworks (CSR, SSR, SSG, and beyond) impact crawlability and performance. In this article by Carlos, you’ll discover hands-on techniques to test, troubleshoot, and optimize how Google and LLMs actually process your pages.

Rendering is one of the most complex aspects of SEO to understand, and this is because you need to have a very solid and clear foundation in how a website works.

It's inevitable to think about JavaScript when rendering is mentioned within SEO. But rendering is much more than that, and many elements are involved in this process.

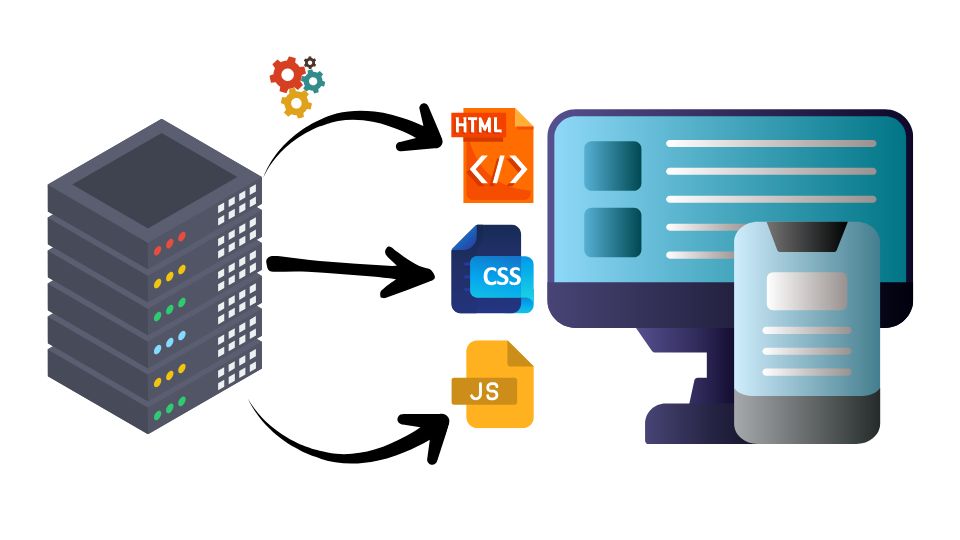

The server always sends different resources to the browser: HTML, CSS, JS, and various types of multimedia files.

The result of all the resources together is what builds a final page and ultimately how it renders in a browser (and in search engines).

So let's take an in-depth look at resources other than JavaScript that can affect our final rendering.

The server is a key part of a website. There's a rendering "pre-process" by the server's programming language to send a resulting HTML.

The key is, since with certain adjustments using a server language such as PHP (this can also be done on websites with Python, Java, or Ruby) we can modify the content of the final HTML before it's sent. This way, users, search engines, and LLMs alike will see exactly the content we want them to see.

What am I trying to say? That there's a trick we SEOs can request from developers when they tell us, "the implementation you're asking for can't be done in this page's code" (with the exception of websites with modern JavaScript frameworks, for which we'll now propose different solutions).

This trick is called modifying the "output buffering". What you do is "hold" the final HTML that was going to be sent to the user and make necessary modifications BEFORE it reaches the user.

Thanks to this type of implementation, we can achieve useful SEO changes that are much cleaner than when they're done with JavaScript.

The reason it's cleaner is because when modifications are made with JavaScript, what we do from the server is send the user an HTML that we modify in real-time in their browser. That is, initially the original code would be "printed" and then the modifications we want to make—if you keep reading the article, you'll understand why this can be a problem.

To get straight to the point and not get sidetracked, what can we do thanks to the buffer?

⚠️Important warning:⚠️ This is a temporary solution, not a good long-term architectural practice. Additionally, buffering can consume server resources, so it's important to limit it properly with switch cases, and, whenever we have the option, it's better to make the change directly in the code. But this is a good solution when we can't find another alternative, definitely better than making those changes with JavaScript in CSR.

In other words, with this practice, regardless of the page's logic, we can remove JS and CSS from pages where those elements won't be used (and thus improve our website's speed), modify headers, or generate an automatic linking system through CTAs quickly and automatically.

What it allows us to do is make any change that we could make with JavaScript (except for interaction) and have it appear directly to the user in their initial HTML, as if there had never been a change, as if it had always been there.

Here's a cross-platform example that works for Drupal, WordPress, PrestaShop, and Laravel:

ob_start(function ($buffer) {

$is_home = ($_SERVER['REQUEST_URI'] == '/' || $_SERVER['REQUEST_URI'] == '/index.php');

if ($is_home) {

$buffer = preg_replace_callback(

'/]*)>/i',

function ($matches) {

$attributes = $matches[1];

if (preg_match('/class=["\']([^"\']*)["\']/', $attributes, $classMatches)) {

$existingClasses = $classMatches[1];

$newClasses = trim($existingClasses . ' buffering-is-working');

$attributes = preg_replace(

'/class=["\'][^"\']*["\']/',

'class="' . $newClasses . '"',

$attributes

);

} else {

$attributes .= ' class="buffering-is-working"';

}

return'';

},

$buffer

);

}

return $buffer;

});

register_shutdown_function(function () {

if (ob_get_length() > 0) {

ob_end_flush();

}

});

Where to place this example code (I recommend to try just in local or staging projects):

So this means that no matter how complicated the website is, we can achieve changes quickly and efficiently, allowing us to remove elements at will. No more being cheap with the classic "display:none" or removing them from the DOM through a JavaScript patch.

Furthermore, this allows us to make mass changes across the entire website, considerably speeding up implementations.

If this type of implementation is done alongside a good cache implementation, it can save a lot of time allowing for quick implementations, even if the website uses drag and drop systems like Elementor or Divi.

Neither Google or users will experience it as if there had been a change, the HTML that reaches them will simply arrive with the changes already made. They will not know about any delay.

As mentioned, the last real-time change to the DOM in the user’s browser — despite its impact on UX — can still work to modify content as long as the original HTML remains indexable.

This is also the reason why certain SEO configurations, such as structured data or even a noindex directive, can be successfully implemented through Google Tag Manager (GTM).

Since Google executes JavaScript during its rendering phase, any change that affects the final rendered HTML — including meta tags, JSON-LD, or canonical updates — will be seen by Google’s Web Rendering Service (WRS), as long as it happens within the 5-second rendering window.

When we think about advanced issues like rendering, we tend to focus on the difficult aspects and forget about the basics.

The basics don’t just mean something is ‘simple,’ but rather that it forms the foundation. Our website’s content is built on the foundation of HTML, so to avoid rendering issues for both browsers and, ultimately, search engine crawlers and LLMs, we need to respect web standards.

I'll share some tricks to keep in mind.

The HTML that the server delivers doesn't have to be the same as what the user sees, since JavaScript makes modifications.

However, the initial HTML that the server delivers is very important for rendering purposes.

For example, that HTML must be indexable (index tag and self-canonical or no canonical at all), because if Google considers the page non-indexable when crawling it, it won't take that page to the rendering process, it will directly consider it non-indexable, even if JavaScript later changes the content of the canonical or the indexation meta tag.

However, the reverse process would work. You can mark the page as indexable and if it's later modified with JS to be non-indexable, the page ends up being non-indexed.

So based on that principle, we must achieve at all costs that the initial HTML is considered indexable.

Therefore we must avoid the word "404" in the title or h1 (even if we're talking about the 404 best tips on any topic), since the page might automatically be detected as a "soft 404" and considered non-indexable, which means it would never reach the rendering process.

There's also another basic HTML issue we must keep in mind both in the initial and final HTML, which is that in the tag we should only put HTML tags that are valid inside the head, otherwise any browser (including headless Chromium, which Google uses) will automatically close the head tag.

No, I haven't gone crazy, CSS affects rendering.

We must take into account non-visible or hidden elements that are shown through interaction (that's why I recommend using summary details in HTML over other "Click and show/hide" configurations that can be done with JS, since we have a native option that serves that same purpose and is compatible with all browsers). But there are other CSS issues that can affect us greatly, specifically regarding Google.

When Google renders, it doesn't scroll or interact, it does so with a simulation of giant devices, both on mobile and desktop.

In fact, it does so with exact heights. On mobile it does so with exactly 1750px height and on desktop with 10,000 pixels height—something that causes a very common error on websites: the vh and dvh error in the "hero" (the hero is the area at the top of a website that acts as the first visual impression, where there are usually sliders, videos...).

When in the "hero" you set 100vh (a measurement to mark the entire height of the device) without any max-height, when Google renders it, it generates a very big problem, since that "hero" ends up occupying the entire "main content", creating a rendering problem in the sense that the true main content is hidden and isn't considered as the relevant part of the page.

This can cause Google to consider your content as "Crawled: currently not indexed".

This causes what's known as "thin content". While in a very well-established brand it doesn't usually generate as much of a problem when it appears on the home page because due to the authority, Google may still consider it relevant (the amstel.es page ranks first for the brand despite being blocked by a robots.txt).

Having a "100vh" without a max-height can cause products or PLPs to be irrelevant and even not indexed since the real "main content" is below its capture.

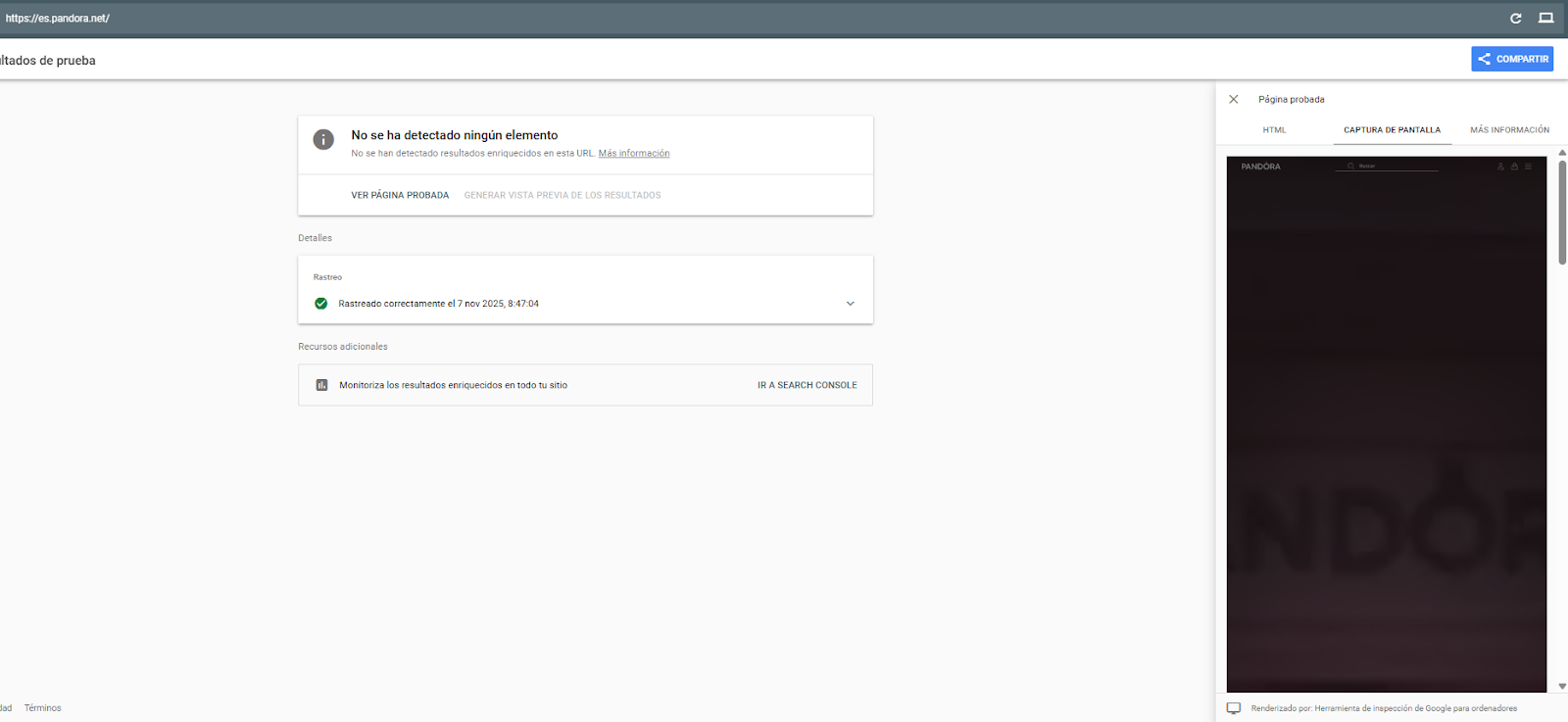

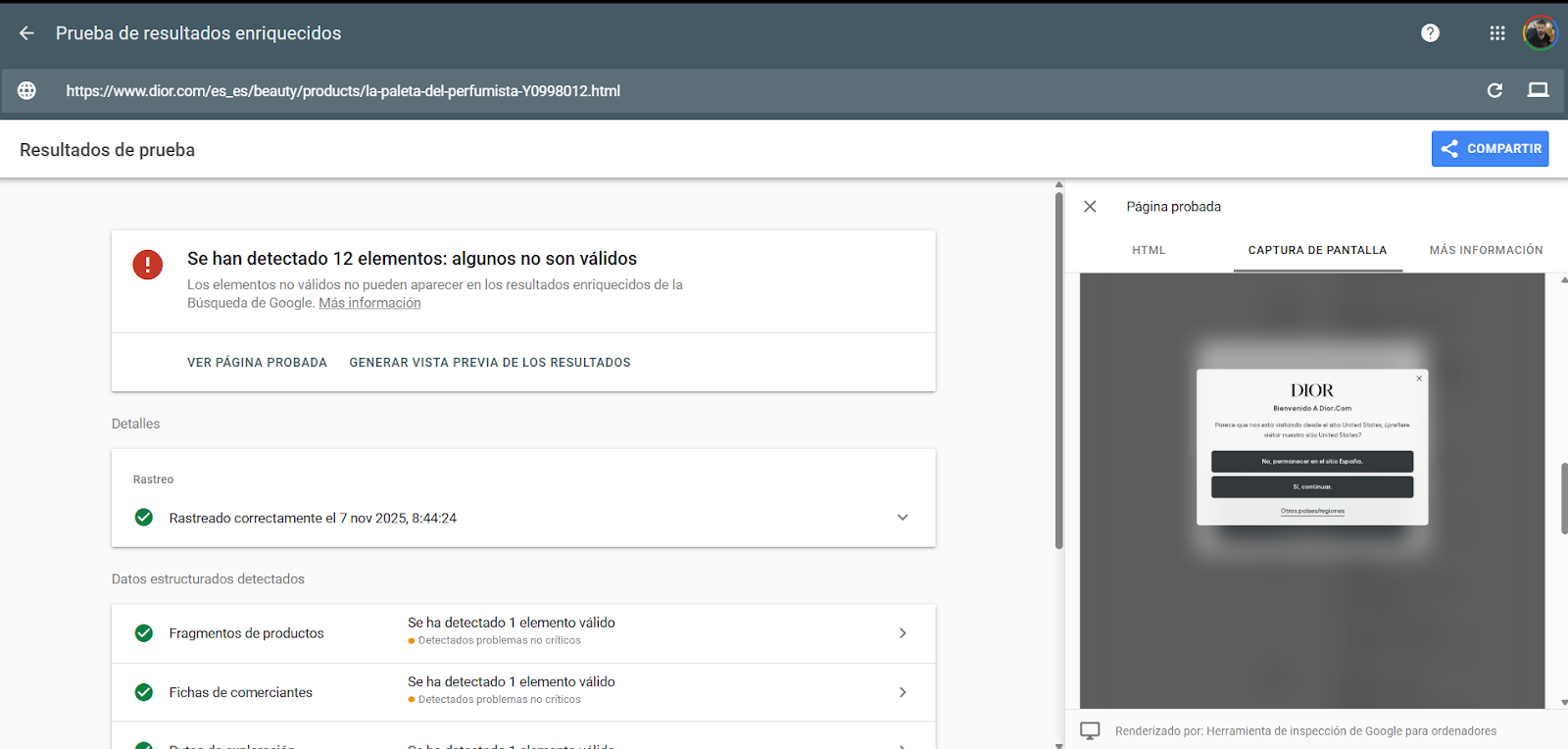

Here I can show you how this happens, for example, on the Pandora page. If we don't have access to Search Console, we can see how Google renders using the rich results testing page.

There are also CSS-based tricks to display visual text content without it being considered as actual text (the inverse of using display:none or visibility:hidden, but still effective).

You can insert content that is perceived as decorative through pseudo-elements like ::before or ::after, which will not be counted as text by search engines.

This means it won’t be considered part of the rendered text content, even if it’s visually visible to users.

Without needing to use data-nosnippet, this text also won’t appear in rich results or featured snippets.

WPO can also affect rendering.

Martin Splitt confirmed that Google takes around 5 seconds to make the snapshot (to capture the main DOM changes).

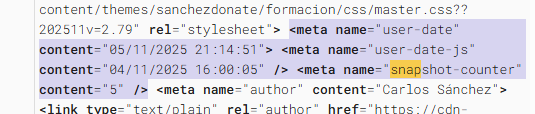

I myself have done tests on several projects with a JavaScript counter in invented meta tags. The response Google gives is always exactly 5 seconds when rendering.

This means that EVERYTHING that takes more than 5 seconds to appear through JavaScript are elements that Google won't see. (I hope you won't be bad and take advantage of this to do some kind of "cloaking".)

Regardless of the methodology used by browsers, search engines and even LLMs to render, your website also uses different methodologies to serve its content, and therefore render it.

On classic websites there's usually not much mystery, but nowadays there are multiple ways to serve content, and some of them are more "SEO-friendly" than others.

Interestingly, the pages most affected by rendering issues are websites built on some JavaScript framework.

Regardless of whether you use Next, React, Angular, Vue or similar, these are the most common types of rendering in the world:

| Type | Description | SEO Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | Render in the browser with JS | Flexible, fast if managed well | Risk of empty content for Google if JS fails |

| SSR | Renders to the server on every request | Visible and indexable content from the start | Loading to server; requires hydration for SPA |

| Dynamic rendering | CSR for users and SSR for bots | Fast solution for LLMs (if you do not care about CSS or functionality) | Discouraged by Google |

| Hybrid | Combine CSR, SSR and SSG as appropriate | Very flexible depending on the content | Complex to implement and maintain |

| SSG | Generate static HTML in build | Very fast and efficient | Not suitable for dynamic content |

| DSG | Render on demand and cache | Web speed | Less customizable than ISR |

| ISR | Renders statically and revalidates on access | Website speed, scalability, and customization | Best option if you can choose for a large project |

Table source: https://carlos.sanchezdonate.com/en/article/javascript-renderings-in-seo/

Editor’s Note: If you’d like a deeper look at how each rendering type compares, including newer approaches like Islands Architecture, check out Matt’s companion article.

You need to keep in mind that LLMs don't render JavaScript, but Google does; and when Google does it, you must keep in mind that Google renders the JS, but doesn't interact with it or scroll.

I wouldn't say that CSR isn't good for SEO at all, especially if what you're focusing on is Google. But you have to make an extra effort, especially focused on rendering.

It's imperative to remember that all pages must be indexable before being rendered in JS (a very common mistake is putting canonicals pointing to the home that are later modified in the DOM, but it's an error because initially only the home would be indexable).

If you want some tips to improve the WPO in JS Frameworks:

While we’ve covered how Google renders JavaScript and the 5-second snapshot window, there are specific JavaScript implementation issues that can severely impact both user experience and how search engines process your content.

Long Tasks are JavaScript executions that block the browser's main thread for more than 50ms. During this time, the browser cannot respond to user interactions like clicks or scrolls, creating a frustrating experience.

From an SEO perspective, Long Tasks are particularly problematic because:

Solutions for Long Tasks:

Web Workers allow you to execute heavy JavaScript operations in background threads without blocking the main thread. This is particularly useful for data processing, complex calculations, or any operation that doesn't directly manipulate the DOM.

One of the most common mistakes in modern JavaScript frameworks is shipping massive bundles filled with code that users never execute. This directly impacts your Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) and Time to Interactive (TTI).

Why this matters for SEO:

Google's rendering process has limited resources. Large bundles mean longer parsing and execution times, reducing the likelihood that your content will be fully rendered within the critical 5-second window.

Solutions for Large Bundles:

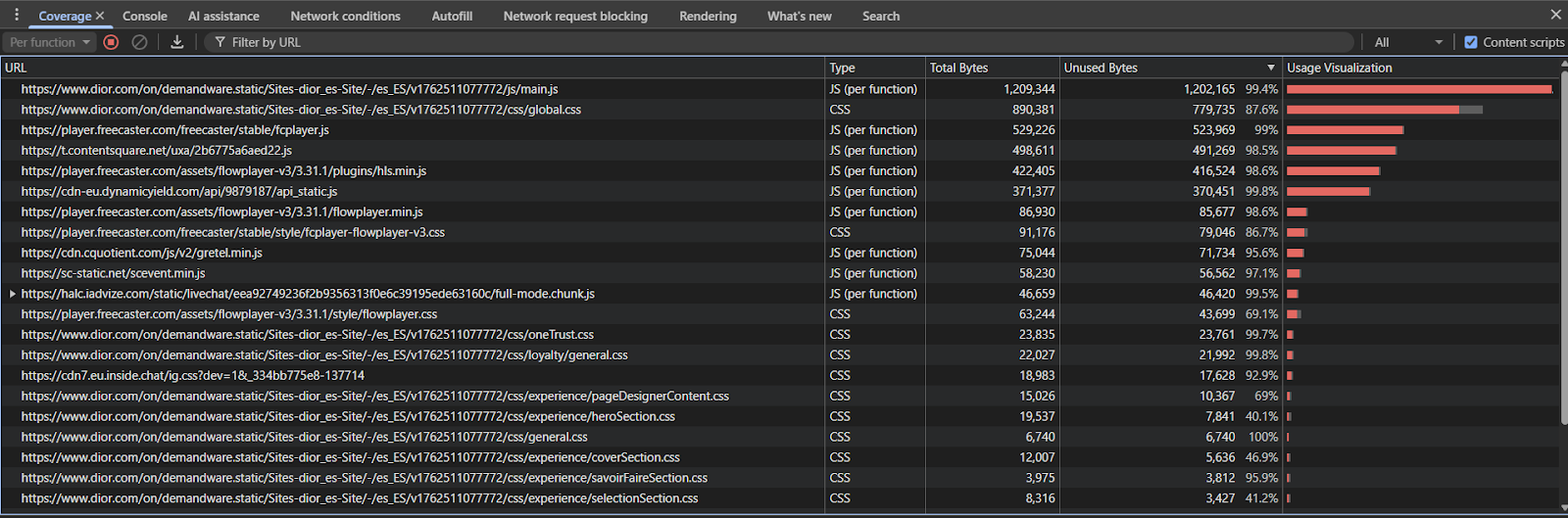

Use the Coverage Panel in DevTools to identify unused code. In Chrome DevTools, open the Coverage panel (Cmd/Ctrl + Shift + P → "Coverage") and record a page load. Red sections indicate code that was downloaded but never executed.

Implement Tree Shaking in your build process. Modern bundlers like Webpack, Rollup, or Vite can automatically remove unused exports if you're using ES6 modules.

Ensure your main content doesn’t depend on lazy-loaded or dynamically imported chunks that take too long to load. The initial HTML should contain meaningful content, even if some interactive features load later.

Note that you can also use Sitebulb’s Code Coverage Report to identify unused snippets of code that can be removed to improve performance.

Hydration is the process where server-rendered HTML becomes interactive by attaching JavaScript event listeners. When poorly implemented, it can cause performance issues and rendering discrepancies.

If hydration takes too long, users (and Google's crawler simulation) might see non-interactive content or experience layout shifts when JavaScript finally executes. This affects your CLS (Cumulative Layout Shift) metric.

Hydration mismatches (when the server HTML differs from client JavaScript) can cause content to flicker or change, confusing both users and search engines about your page's actual content.

Progressive Hydration prioritizes hydrating visible and interactive components first, deferring less critical elements.

Islands Architecture (implemented in frameworks like Astro) treats interactive components as isolated "islands" within otherwise static HTML. This minimizes the JavaScript shipped and executed.

Resumability takes a different approach: instead of re-executing all your JavaScript to recreate the application state, it serializes the state on the server and resumes it on the client without hydration.

Best practice for SEO:

Whatever hydration strategy you use, ensure your initial server-rendered HTML is complete and accurate. Google crawls the initial HTML first, and if it's indexable and contains your core content, you're already in a good position even if hydration hasn't completed during the 5-second rendering window.

If you've made it to this point in the article, you already have a very good foundation about rendering. So now we're going to synthesize the most important points to achieve the best results when we work on SEO.

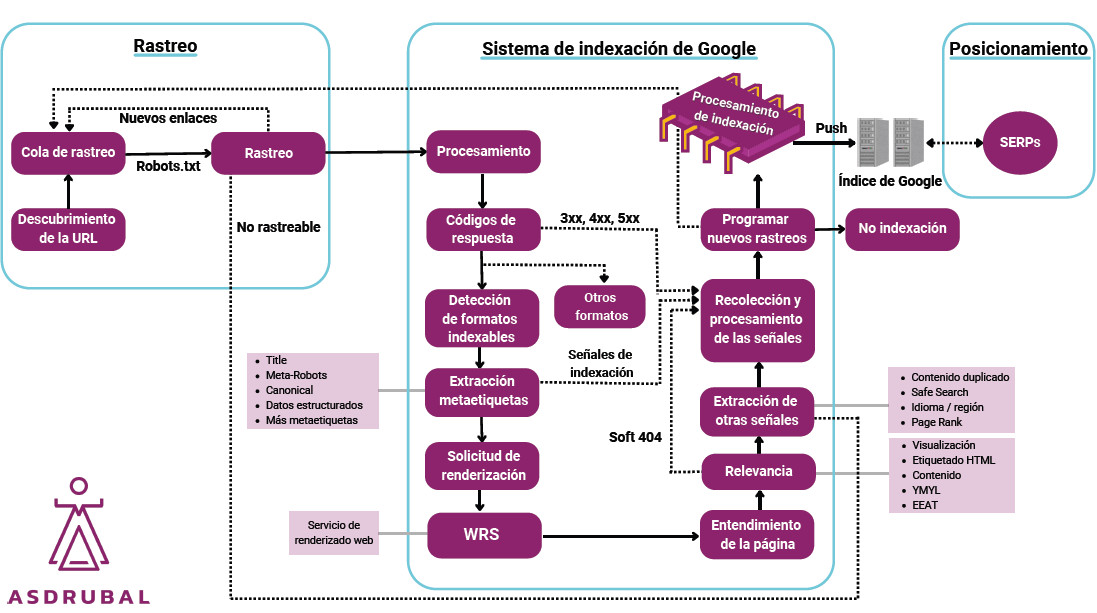

Google first crawls content without JavaScript (it's much more efficient). Then it has a microservice called "WRS" (Web Rendering Service) that uses headless Chromium to render pages with the cached content from those pages.

This means that the moment of rendering and crawling are not the same, and we won't see the rendering moment in our website logs.

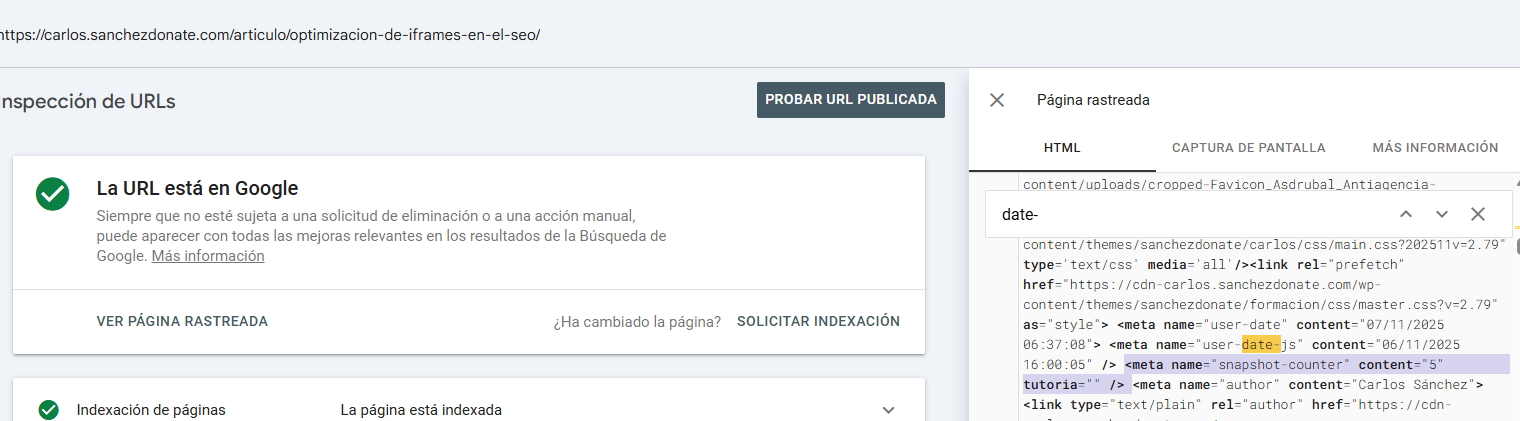

I recommend adding some custom meta tags that serve me well:

This way I can track exactly the timing behavior on my website when I inspect a URL from Search Console.

To audit Google's rendering, I recommend using Search Console for your own projects and the rich snippets test for projects where you don't have Search Console access - it's the most accurate. Although other tools (like Sitebulb’s Response vs Render Report) can help us.

In php the code to do this would be something like this

$date = date('d/m/Y H:i:s');

date_default_timezone_set('Europe/Madrid');

?><meta name ="user-date"content ="">

<meta name ="user-date-js"content ="">

<meta name ="snapshot-counter"content ="0">

For date:

function updateMetaDate(){const metaTag = document.querySelector('meta[name="user-date-js"]');

if(metaTag){setInterval(()=>{const now = new Date();

const formattedDate = now.toLocaleString('es-ES',{year:'numeric',month:'2-digit',day:'2-digit',hour:'2-digit',minute:'2-digit',second:'2-digit'}).replace(',','');

metaTag.setAttribute('content',formattedDate)},1000)}}

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded",updateMetaDate)

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', () => {

const meta = document.querySelector('meta[name="snapshot-counter"]');

let count = parseInt(meta.getAttribute('content')) || 0;

const intervalId = setInterval(() => {

count ++;

meta.setAttribute('content', count.toString());

console.log('time a:', count);

const currentValue = meta.getAttribute('content');

console.log('Dom value:', currentValue);

}, 1000);

window.snapshotIntervalId = intervalId;

});

This tool helps us verify rendering, including the DOM, server response, and visual appearance.

"URL inspection" is not the same as "test live URL." (It's worth remembering that you can "test live URL" on any website using the structured data testing tool).

URL inspection helps us check what Google actually saw, while the "live test" or "test live URL" helps us verify how it would look (in theory) if the crawler passed through. It's also useful for checking the visual appearance.

The "screenshot" helps us as humans to see how it would look and how it's interpreted. The fact that it doesn't reach the footer means it's not needed for rendering—Google will see everything, but it shows us what it considers an estimation of the main content. In theory, the main content shouldn't be that far down either.

This tool, beyond rendering, can also be used to check "paywalls" and "age gates."

Remember that Search Console doesn't use exactly the same IP range as Googlebot does for ranking, so it's possible that when you run the live test, you'll see something different from when you inspect a URL.

Standalone LLMs (ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity) are currently incapable of rendering JavaScript. (You can learn more about this in Sitebulb’s The Search Matrix series: advanced SEO training for the age of AI.)

Therefore, pages that don't serve any content in CSR miss out on the opportunity cost of appearing on these platforms, at least in an efficient way.

A viable option, especially for LLMs in the case of wanting to have a JS framework website without an optimized SSR version or derivatives, would be the "dynamic rendering" option, selecting only the user-agents of LLMs designed to serve them that content.

You need to be careful because not all LLMs use recognized user-agents. For example, Grok uses the iPhone user-agent but without JS.

Rendering in SEO goes far beyond JavaScript. It is the full process by which browsers, search engines and LLMs interpret your HTML, CSS and JS to understand your content.

In fact, I’d like to point something out. The acronym SEO is misleading—we don’t optimize search engines; we optimize websites so that they perform better across different search engines (including whatever you call the LLMs).

And rendering, to a large extent, focuses on observing, analyzing, and correcting whether our implementations – or even our entire website – are actually readable by those different search engines.

I recommend you to read all the article to have the real context and useful explanations you will be able to apply in your projects, but here you have the main points:

Rendering isn’t just technical—it’s strategic. The closer your delivered HTML matches what users and crawlers should see, the better your site performs in both SEO and LLM discovery.

I currently offer advanced SEO training in Spanish. Would you like me to create an English version? Let me know!

Tell me you're interested